In this essay, Huw Owen of the Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC) - which now has a full time presence in Scotland - discusses the contemporary challenges of delivering humanitarian aid, and why the collaborative approach of the DEC optimises the delivery of assistance to where it is needed across the world.

For those of us who have become adept at ducking the commercial and consumer imperatives of the Christmas period, there is perhaps a little more time to reflect not only on the religious basis of this celebration but also on its power to unite families and communities, and to open our minds and hearts to those less fortunate than ourselves.

In the humanitarian community too, it’s a time to reflect on our efforts to save lives and rebuild families and communities devastated by natural disasters or conflicts, about why and how we do it. I’m struck by one of the most engaging and emotional of modern Christmas stories, Frank Capra’s 1946 film, It’s A Wonderful Life, and the message at its core about ‘second chances’.

While there are numerous reasons why people may choose to support humanitarian causes, I’m convinced many of us are driven by the power of giving or receiving that second chance.

A colleague experienced in years of hazardous and harrowing work delivering aid through the Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC) was asked by a sceptic about his continued motivation. Wasn’t it inevitable that, despite his efforts, thousands may still die or just as likely, he would return to the same place in years to come, with solutions to poverty and ill health remaining elusive? His reply was simple: “When I see a child who I know would not have been alive without our support, the knowledge that I’ve helped give them a second chance of life is motivation enough.”

That motivational power has helped sustain the Disasters Emergency Committee and inspired millions to donate to this British institution for more than 50 years. That is of course codified through the ‘humanitarian imperative’ - which guides all NGOs at times of crisis - as every person’s right to receive and to give humanitarian assistance, and asserts the obligation of the international community “to provide humanitarian assistance wherever it is needed.”

We also hope that the way we work inspires people to support us. From an understated office in a back street near Euston station in London, just 20 staff are at the heart of an incredible network of care. With the support of all the major broadcasters, our 13 member agencies and countless others, this network brings in donations worth tens of millions of pounds every time we take the big decision to ask the public for support.

CHANGING PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS

However, we do not take this support for granted. With the 2008 financial crisis continuing to reverberate, limiting the take-home pay of millions of people, it’s understandable that some react to inequality and austerity by supporting protectionism and isolationism. This has been accompanied by a breakdown in trust in once-sacred institutions: not only governments and parts of the City, but also many other public bodies. Charities are not immune to this shift in the public mood and it is more than understandable that donors demand accountability and appropriate scrutiny of money that is donated to saves lives.

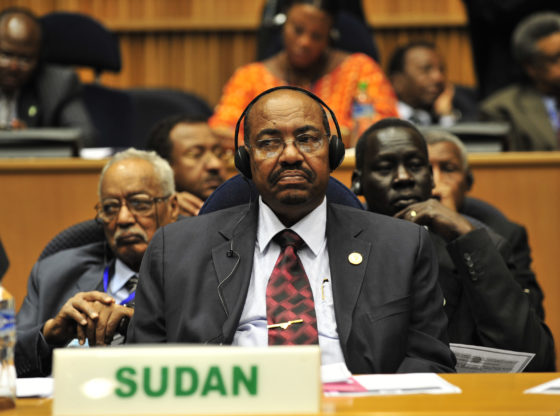

The DEC also has to adapt to rapidly changing geopolitics and an upsurge in large scale, cross border inter-communal violence. Climate change, urbanisation and, of course, technology are also having a huge impact on the scale, size, and frequency of humanitarian crises.

The DEC also has to adapt to rapidly changing geopolitics and an upsurge in large scale, cross border inter-communal violence. Climate change, urbanisation and, of course, technology are also having a huge impact on the scale, size, and frequency of humanitarian crises.

This complexity, and the multiplicity of players involved in relief efforts, can be accompanied by bureaucracy and competition between aid groups which, of course, can blunt collective efforts and weaken confidence in the humanitarian sector. That is where the DEC and the power of networks comes in with its straightforward maxim: Together We Are Stronger.

THE IMPORTANCE OF A COLLABORATIVE APPROACH

In a crisis, people donating money want to know that their money is going to go as quickly as possible to where the need is most acute. The DEC, and indeed many similar models around the world, work for the following reason: we provide a clear one-stop shop that makes it easier for people to both understand the crisis they’re being asked to support, and take the guesswork out of giving.

With the wealth of professionalism and experience that comes from our member agencies, knowledge-sharing on the ground drives ever improving standards and the effectiveness of our response. Working together saves duplication, drives down fundraising costs, provides a single focal point for media interest, whilst also increasing the chance of building support from powerful partners. That collective DEC reputation can attract strong corporate backing too. When faced with competing requests, many donors and businesses may decide not to make a contribution at all.

WORKING HARD ON THE GROUND

This approach has informed our response to the complex crises over the past twelve months in Yemen, East Africa, and for people desperately fleeing Myanmar into Bangladesh. For those people who rarely get the attention they need and deserve, the DEC in partnership with the British public, has raised more than £100 million for these 3 crises.

In Yemen, where civil war still grips one of the poorest countries on earth, the funds we’ve raised should help nearly one-and-a-half-million people in the next eighteen months. Tackling cholera as well as malaria still presents a huge challenge, so much of the focus is on providing water and basic sanitation.

In extremely hazardous conditions, member agencies are providing food and medical supplies, but have an eye on future resilience too, so they’re rebuilding infrastructure - for example, installing solar powered water supplies. Whilst our member agencies work ever more closely through the DEC network, they in turn are building front-line networks with the help of local leaders and volunteers to build longer-term capacity, all reflecting the increasing emphasis on future planning, aligned with community and country priorities.

Another increasingly significant focus is on cash transfers and food vouchers. Transferring money is much more efficient than transporting supplies; it supports local markets, again giving local people more choice and control. Money can also be targeted at those at the bottom of the local caste system, in Yemen’s case at the Muhamesheen, who are often targeted or nearly always disproportionately affected during humanitarian crises. All these interventions are supported by improved data gathering with smartphones, which are also being used to help on-the-ground communication through local networks.

Transferring money is much more efficient than transporting supplies; it supports local markets, again giving local people more choice and control. Money can also be targeted at those at the bottom of the local caste system.

In East Africa, where 19 million people are threatened by drought and conflict in Ethiopia, Kenya, South Sudan, and Somalia, funds will provide relief to another one-and-a-half-million people. It will provide them with food and clean water as well as feed for their animals. Like in Yemen, women, children and the elderly are particularly vulnerable, so many of the agencies are prioritising them in treating acute malnutrition and providing cash and vouchers so they can decide what basic items they need to survive in the harshest conditions.

In Kenya and Somalia, where there are now relatively advanced mobile banking networks, money transfer is flexible and fast, and offers a sensible alternative in often highly dangerous and logistically extreme environments.

THE ROHINGYA CRISIS

Our recent appeal for the mostly Rohingya people fleeing in terror from Rakhine province in Myanmar may not be quite on the same scale as this year’s other crises. But take just one look at the incredible drone footage the DEC obtained from the Bangladesh border camps and it becomes much clearer why we decided to launch a rare third appeal in just 12 months.

“New types of violence and torture, worse than anything we’ve seen before” have been used against Rohingya women.

Some of my colleagues have just returned from the border and can scarcely believe the repeated stories of the most primal savagery that these stateless people have been subjected to. As is so often the case, it is women and children that dominate the squalid camps. In the past few days, the head of UN Women, Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka said “new types of violence and torture, worse than anything we’ve seen before” have been used against Rohingya women. Whilst perhaps not as arresting as images of an earthquake or a tsunami, more than half a million people have had no option but to risk the most extreme journeys - through forests, across swollen rivers, or even by ramshackle fishing boats across the Bay of Bengal - in order to save their lives.

The DEC agencies’ speed of response has already had an impact. The logistical effort to get aid to families perched in precarious hillside shelters, through stifling heat or monsoon rains, has been heroic. What may seem less heroic - but is in fact critically important - is the building of toilets, which we have been doing with some urgency. We may not imagine that providing sanitation to support health is a top priority, but it is in fact strategic thinking, effectively reducing the risk of deadly waterborne infections like cholera.

The network effect has once again been crucial to the response, with UK agencies increasingly working with ever local agencies to co-ordinate what is needed, where and when. Another DEC colleague remarked that amongst the roads and paths clogged with aid deliveries, it was remarkable to witness the calmness and dignity of these people who have endured so much. Perhaps it is in their character and culture, perhaps they’re dumbstruck by their ordeal, or maybe it’s sheer relief that they have escaped their pursuers and been given that second chance at life.

DRAWING LESSONS HERE IN SCOTLAND

Amidst this chaos, there are lessons which can inform how we should, and how we will, work back here in Scotland. The DEC has raised huge sums here throughout its history but hasn’t until now ever had a full-time presence in Scotland. As elsewhere, our Scottish member agencies - Tearfund, Christian Aid, Oxfam, Save The Children, Islamic Relief, and the Red Cross - remain squeezed. In this climate, the DEC believes that its tried and tested network model is fit for the challenges ahead, and can thrive amongst the broader Scottish development community to build support from a very generous Scottish public.

In the first report of its kind, the Charities Aid Foundation revealed in October that Scots, on average, are that bit more generous when it comes to supporting charity. The report says that’s no great surprise given the “culture of giving that is so deeply embedded within Scotland.”

As CABLE magazine demonstrates and promotes, Scotland is not only generous but also has a proud history of internationalism. While the devolution settlement limits what the Scottish government can do internationally, the government in Edinburgh does support some inspirational networks of influence and action that are making a real difference to lives in the ‘global South’, and those afflicted by natural disasters or conflict.

One of the most striking examples of the power of networks is the Scottish Malawi Partnership (SMP), with nearly 100,000 Scots who have active links to the impoverished landlocked African nation. The emphasis of SMP is firmly on partnership and not just handouts. The Partnership doesn’t like to talk about donors or recipients: it prefers to talk about partnership and friendship, about building connections and collaboration that can be transformational. This model may well be unique worldwide.

The Glasgow Centre for International Development (GCID) at Glasgow University is a great example of how educational expertise can be harnessed not only in supporting disaster recovery and resilience, but across the wider development agenda.

We are also lucky to work alongside a wider network of influence in the newly named Scottish International Development Alliance (formerly NIDOS). There are more than 100 organisations, small and large, across Scotland who recognise that the power of its network comes from ever closer co-operation both here in Scotland and overseas, with support from the private sector and academia. It’s great to see universities taking active steps to bring their huge knowledge and skills to this cause. The Glasgow Centre for International Development (GCID) at Glasgow University is a great example of how educational expertise can be harnessed not only in supporting disaster recovery and resilience, but across the wider development agenda.

We are also delighted that the Scottish government has now formalised its support for rapid humanitarian action with the establishment of the £1 million Humanitarian Emergency Fund. This has not only directly helped the DEC in our most recent appeals, but also directly supports our member agencies with their aid efforts. With the ongoing support of Westminster through its Aid Match scheme, that is a strong platform for the DEC to build on. It’s becoming increasingly clear that mutually supportive networks built on experience and trust, harnessing both the emotive power of face-to-face dialogue and the simplicity and reach of the internet, can not only help us improve humanitarian response but also have wider societal benefits.

We are also delighted that the Scottish government has now formalised its support for rapid humanitarian action with the establishment of the £1 million Humanitarian Emergency Fund.

One of the leading thinkers on networking in the digital age, Australian writer and researcher, Rachel Botsman, argues that trust is leaching from institutions and instead becoming distributed through networks of individuals. She posits that institutional trust can be top-down, centralised, licensed, closed, and opaque. In contrast, trust distributed through networks of individuals, (think AirBnB, with some reservations!) is bottom up, decentralised, accountable, inclusive, and transparent. Whether you’re with a hitherto revered institution or work alone, these are interesting questions to ponder as we prepare for the challenges to come.

Sadly, there is little doubt the imperative to provide humanitarian relief will remain strong. Indeed, the next complex conflict or natural disaster could only be days away. So the DEC will keep working hard to build effective networks and do whatever it can to give those who have nothing a second chance.

Huw Owen is External Relations Manager, Scotland, with the Disasters Emergency Committee.

Feature image: Carrying water in Yemen. © Disasters Emergency Committee.