Following the conviction last month of Ratko Mladić at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, Norrie MacQueen considers the background and consequences of the atrocity most associated with his name: the Srebrenica massacre of 1995.

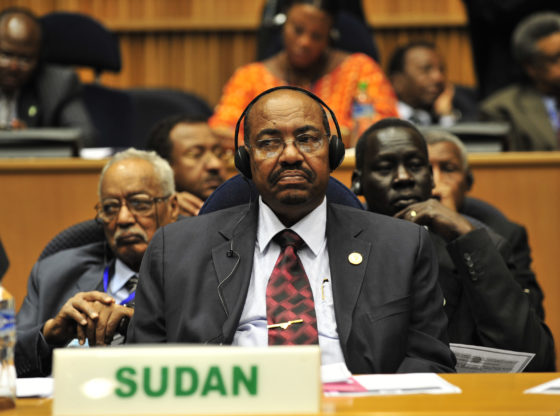

Hannah Arendt’s famous phrase ‘the banality of evil’ was originally applied to Adolf Eichmann, the monstrous apparatchik of the Holocaust, to describe the unprepossessing mediocrity facing trial in Jerusalem in 1961. But it was absolutely spot-on last month when we watched an angry old man spluttering obscenities and being ushered from the chamber of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) at The Hague. Ratko Mladić, the so-called ‘Butcher of Bosnia’ did his best to summon up the swaggering menace of his glory days, but at the end he was merely pathetic.

He was the last of the unholy troika that engineered terror across Bosnia in the 1990s to face justice. After the end of the Bosnian war in 1995, when international revulsion at the events at Srebrenica - and other Bosnian Serb atrocities - finally triggered decisive action, Mladić was protected first by the Serbian-Yugoslav military and then, as the political sands began to shift, by hard-line nationalist supporters in remote Serbian villages. Finally captured in 2011, his trial at the ICTY began the following year. Last month, the verdict and sentence were finally pronounced. He was found guilty on one count of genocide, five of crimes against humanity, and four of violations of the laws or customs of war. The sentence was life imprisonment, and although he is to appeal, there’s little doubt that the seventy-four year-old will end his days in jail.

While Milošević was a failed Machiavelli de nos jours, and Karadžić was always a fundamentally ridiculous character, Mladić had a genuine capacity to chill the blood.

Mladić’s puppeteer during the war, the Serbian Yugoslav president Slobodan Milošević, had died in detention while on trial at the Hague in 2006. His supposed political master, the president of the Bosnian Serb Republika Srpska, Radovan Karadžić, was sentenced by the Tribunal last year to forty years in prison. While Milošević was a failed Machiavelli de nos jours, and Karadžić was always a fundamentally ridiculous character, Mladić had a genuine capacity to chill the blood. Nowhere had this been in evidence more than at the supposed United Nations ‘safe area’ of Srebrenica, in July 1995, as he prepared the massacre of 8000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys.

Srebrenica came to define the singular evil of the mosaic of conflict that followed the breakup of Yugoslavia. Ultimately, Srebrenica was the unifying element in the indictments faced by those three major criminals at The Hague.

THE UNRAVELLING OF YUGOSLAVIA

The road to Srebrenica in 1995 had been long and tortuous. It began in 1991, seventy-two years after Yugoslavia’s creation as a multi-ethnic state following the defeat of Austria-Hungary in the First World War. During that year, two of its most important federal units, Slovenia in the north and Croatia in the west, unilaterally proclaimed their secession and independence. Yugoslavia had been critically unstable since the death of its long-term leader Josip Broz Tito in 1980. Tito had led the resistance to Nazi occupation during the Second World War and then held Yugoslavia together as a non-aligned socialist state through the cold war years. By the beginning of the 1990s, however, the old bases of Yugoslav unity were crumbling. At the same time, the winds of change in central Europe were blowing in from the east as Soviet power ebbed.

By the beginning of the 1990s the old bases of Yugoslav unity were crumbling. At the same time, the winds of change in central Europe were blowing in from the east as Soviet power ebbed.

Slovenia’s independence was won relatively easily, at least in comparison to what was to come later elsewhere. Its salvation lay in its relative ethnic homogeneity. It was essentially a unified Catholic nation of western Europe with obvious affinities to its neighbours, Italy and Austria. This was not the case in Croatia, however, where the war of independence proved long, bloody, and a harbinger of what was to come further east in Bosnia. In Croatia, ethnic Serbs made up around 12 percent of the population when, in June 1991 under its nationalist president Franjo Tuđman, it declared independence. In the ensuing violence Croatia’s national forces were pitched against the Yugoslav army (JNA) and civilian gangs became involved on both sides. A new expression soon came into currency: ‘ethnic cleansing’, the forced expulsion (or worse) of minority communities, whether Croats from Serb dominated areas or vice versa.

THE UN INTERVENES

In the autumn of 1991, the United Nations responded by deploying a Protection Force (UNPROFOR). The 14,000-strong peace operation had some success. UN ‘protected areas’ were created so those who had been ‘ethnically cleansed’ from their homes could find refuge. In the meantime though, the war of Croatian secession continued and ended only in 1995, after about 10,000 had died and three quarters of a million people had become refugees.

It became clear during the latter part of 1991, and into 1992, that the disintegration of the Yugoslav state was destined to continue, and that it would be accompanied by horrific levels of ethnic violence. Attention now turned to Bosnia-Herzegovina. Here, the largest ethnic group, the predominantly Muslim Bosniaks, formed only 43 percent of the population of four million. These were concentrated in the centre of the country, including in the capital Sarajevo. About 31 percent of the population were Bosnian Serbs living mainly in rural areas in the north and east, adjacent to the border with Serbia which now formed the major part of what remained of Yugoslavia. This large Serb minority in Bosnia felt threatened by the prospect of independence and these fears were fuelled by the strident nationalism of the Milošević regime in the Serb-dominated rump of Yugoslavia.

Bosnia’s plight was complicated further by an ethnic Croat presence in the western area which comprised about 17 percent of the country’s overall population. Just as the Bosnian Serbs had been infected by Milošević’s drum-beating, the Croat minority had fallen prey to Tuđman’s nationalist rhetoric. The Bosniaks, although the largest single population group, were the only one without the support of an external ethnic ‘motherland’.

BOSNIA DECLARES INDEPENDENCE: THE FUSE IS LIT

In April 1992, the Bosnian leader Alija Izetbegović realised the worst fears of outside observers by proclaiming his country’s independence from Yugoslavia. Three incompatible political objectives were now in play in Bosnia. While the Bosniaks celebrated independent statehood, the Bosnian Serbs were determined to maintain Bosnia in the Serbian-Yugoslav state, and the Bosnian Croats nursed visions of unification with the new state of Croatia.

Fighting broke out immediately when the JNA was ordered by Milošević to support Bosnian Serb militias against the new national army of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The combined Serbian forces - in which Ratko Mladić soon became dominant - quickly took over a swathe of Bosnian territory which became Serbian Bosnia or Republika Srpska.

AN EXPANDED UN MANDATE

The United Nations obviously had to react to events in Bosnia but the crisis in many ways couldn’t have come at a worse time. The UN had commitments in a large number of complex post-cold war conflicts across the world, with the heaviest burdens in Cambodia, Angola, Mozambique, and Somalia. Attempts to persuade other agencies and potential ‘coalitions of the willing’ to take on the burden of Bosnia were unsuccessful. UNPROFOR’s mandate was therefore extended from Croatia to Bosnia.

The UN force was “neither structured nor equipped for combat and (had) never had sufficient resources, even with air support, to defend the safe areas against a deliberate attack …”.

It was a mandate that the UN force was inadequately equipped and empowered to execute. In an attempt to replicate the relative success of the Croatia intervention, in April 1993 the UN Security Council passed Resolution 819 which declared Srebrenica - which was essentially a Bosniak enclave within Republika Srpska - to be “a safe area which should be free from any armed attack or any other hostile act”. Later, the Bosnian capital Sarajevo to the southwest of Srebrenica, and the towns of Bihać, Goražde, Tuzla, and Žepa which were adjacent to Republika Srpska, were also designated as safe areas.

From the outset, however, these areas proved difficult to define and delimit properly, let alone protect. Boutros Boutros-Ghali, the UN Secretary-General, freely acknowledged the scale of the problem. In a report in May 1994, he stated that the safe area concept could only work on the basis of consent and cooperation and this was not forthcoming from the Bosnian Serbs. In the absence of this, the UN force was “neither structured nor equipped for combat and (had) never had sufficient resources, even with air support, to defend the safe areas against a deliberate attack …”.

The Security Council, alarmed at the mounting costs of peacekeeping globally, refused Boutros-Ghali’s appeals for the increased resources that an effective protection operation would have required. Nevertheless, UNPROFOR would do what it could within its capacities to “protect the civilian populations of the designated safe areas against armed attacks and other hostile acts, through the presence of its troops and, if necessary, through the application of air power …”. It was unclear, though, what degree of protection Srebrenica could really rely on.

THE SERBIAN PUSH

For Ratko Mladić and the expansionist project of Republika Srpska, Srebrenica was of special strategic importance. Although formally in Bosnian government hands while designated as a UN safe area, it was under more or less constant siege from Mladić’s forces. Yet for a while at least, the UN presence seemed to deter a full-scale Serb attack. But in mid-1995, Mladić intensified his operations in the region. The Netherlands UN contingent in Srebrenica (“Dutchbat” - the Dutch battalion) was about 600-strong but Mladić’s forces had reduced it over time by stopping peacekeepers who had left the safe area from returning. The UN evidently chose to ignore this breach of a central principle of peace operations: unimpeded freedom of movement. Mladić’s so-called ‘Drina corps’, in contrast, numbered up to 2000.

The backstop to the beleaguered Dutch force was supposed to lie in over-the-horizon NATO airpower. In Bosnia, however, the inter-agency relationship between the UN and NATO was often troubled. The command structure had, perhaps deliberately, been left vague - ultimately, this led to a critical degree of policy dysfunction.

NATO resisted the idea that it was a mere subordinate part of the UN operation in Bosnia. In the words of its Secretary-General Willy Claes, in 1994, it was not to be “a sub-contractor of the United Nations”. This political difficulty was met by creating a so-called ‘dual key’ arrangement which required both organizations to formally agree to any air action conducted by NATO warplanes. If there was a single factor responsible for the tragedy of Srebrenica, it was probably this unwieldy political compromise between the two intergovernmental organisations.

END POINT

The final attack by Mladić’s forces on the safe area of Srebrenica began in the early hours of 6 July 1995. Its fall was complete by the afternoon of 11 July. The worst, most systematic period of massacre then began on the 13th. Repeated requests by Dutchbat for close air support to deter the Bosnian Serb forces were blocked or ‘lost’. This does not absolve the peacekeepers on the ground, of course, but culpability for the Srebrenica tragedy was widely spread. In fact, the UN commander had first asked for close air support even before the Serb assault was fully underway on 6 July: a request was made once more on the 8th. Both requests were refused by UNPROFOR headquarters in Sarajevo.

Events were still raw in the collective peacekeeping memory and the ‘lessons learned’ from Mogadishu pointed towards military reticence as the favoured default stance.

These refusals were decisive. The thinking behind them was that NATO airstrikes might push the confrontation across what had come to be known as ‘the Mogadishu line’. This was the frontier between peace operations and war-fighting, named after the mission creep which had mired the UN’s operations in Somalia two years previously. These events were still raw in the collective peacekeeping memory and the ‘lessons learned’ from Mogadishu pointed towards military reticence as the favoured default stance.

As the situation deteriorated, it became clear that the opportunity for deterrence through air support had passed. A request was made – and in the minds of Dutchbat, agreed to – for not just air support but multiple offensive strikes against Mladić’s positions. These were scheduled for the early morning of 11 July. Had they been unleashed, they may well have degraded Mladić’s resources to a point where his final assault on Srebrenica would have been unviable. But – again – the eagerly anticipated NATO aircraft didn’t appear. It later emerged that the warplanes had been airborne, awaiting final orders to attack. These orders were never received. Running low on fuel, the aircraft were forced to return to their bases in Italy and Mladić was given a clear run into the centre of the UN safe area.

MASSACRE

From this point, the Dutch peacekeepers on the ground began to make some very bad choices. They refused to return weapons they had taken from Bosnian government forces within the safe area, something which might at least have slowed the advance of Mladić’s forces. This contrasted with the actions of Ukrainian UNPROFOR troops in the neighbouring safe area of Žepa, who had taken entirely the opposite course when Bosnian Serb forces attacked there.

But the more serious, indeed unconscionable, failure was the forcible transfer by the Dutch of Bosniak men who had taken refuge in the UN compound to Mladić. This action alone made the UN directly complicit in the massacre that was to follow. To cap off the ignominy, the Dutch UN commander (looking visibly nervous) allowed himself to be filmed drinking a toast with a preening Mladić after the final Serb occupation of the safe area. To the watching world, it was simply outrageous.

Yet hindsight must be applied with caution. There was no reason for the Dutch to believe that Mladić was already planning a crime which Alphons Orie, the presiding judge at his trial, would describe as “among the most heinous known to humankind”.

Although the atrocities at Srebrenica would take many years to catch up with Mladić himself, their impact on the Bosnian war came rapidly. As the extent and details of the massacre emerged, the international community was forced into the decisive action it had avoided hitherto.

Although the atrocities at Srebrenica would take many years to catch up with Mladić himself, their impact on the Bosnian war came rapidly. As the extent and details of the massacre emerged, the international community was forced into the decisive action it had avoided hitherto. A few weeks later, the fate of Mladić’s Bosnian Serb forces was sealed. Perhaps over-confident after having apparently ‘got away’ with Srebrenica, they intensified their artillery and sniper attacks on the civilian population of Sarajevo.

Before Srebrenica, this had been more or less tolerated. But no longer. The UN now moved to the margins and NATO took centre-stage. With the United States - led by President Clinton - fully engaged for the first time, NATO launched a series of decisive airstrikes and artillery bombardments which crippled the Bosnian Serb army. With no feasible alternative available to them, the sides were ‘invited’ to sit down in Dayton, Ohio to agree, if not peace, then at least a cessation of violence.

HARD-LEARNED LESSONS

In the medium term, fundamental lessons – none of them to the comfort of future Ratko Mladićs - seemed to have been learned from the tragic events which took place across the summer of 1995. Four years later, when the first signs of a potential repeat of the Bosnian nightmare began to emerge in Kosovo, NATO moved hard and fast to cauterise the situation. The resulting humiliation for Serbian nationalist ambitions, and the end of the dream of a ‘Greater Serbia’ to supplant Yugoslavia, soon led to the fall of Slobodan Milošević in Belgrade and, eventually, to his transfer to The Hague to face the ICTY.

The UN’s whole approach to its peace operations fell under examination after Srebrenica. The soul-searching was also driven by that other black spot on the peacekeeping project - the 1994 Rwanda genocide. The landmark UN report produced by a panel chaired by Lakhdar Brahimi in 2000 confronted many of the issues raised by both of these horrors. In particular, Brahimi challenged the traditional peacekeeping concept of ‘neutrality’, proposing instead one of ‘impartiality’.

‘Neutrality’ in the sense of “equal treatment of all parties in all cases for all time [could] amount to a policy of appeasement”, and could actually facilitate crimes by constraining intervention on the ground. ‘Impartiality’ would instead mean commitment to the even-handed pursuit of an operation’s mandate. Some interventions, Brahimi noted, take place in situations where the parties “consist not of moral equals but of obvious aggressors and victims, and peacekeepers may not only be operationally justified in using force but morally compelled to do so”. The implications of this observation for the behaviour of the UN in Bosnia generally, and in Srebrenica in particular, were crystal clear.

In 1999, the UN produced the results of its own lengthy and detailed investigation of the Srebrenica massacre, and the lessons that must be learned from it. Introducing the report, Boutros-Ghali’s successor as UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, distilled these into a resonant phrase:

“(t)he cardinal lesson of Srebrenica is that a deliberate and systematic attempt to terrorize, expel or murder an entire people must be met by all necessary means, and with the political will to carry the policy through to its logical conclusion”.

The conviction of Ratko Mladić last month brings to an end the major work of the Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. It has been a satisfying coda. For a long time after its creation in 1993, the Tribunal had little credit or prestige. It appeared to be absorbed with over-lengthy procedures against relatively small fish from the swamps of Yugoslavia’s disintegration. This changed with the appearance of Slobodan Milošević at the Hague in 2002, and then Radovan Karadžić six years later. But it was the trial of the uniquely malign Ratko Mladić, and the life sentence imposed on him, which has fully validated the Tribunal as a foundational institution of international criminal law.

The other special courts set up to deal with major human rights crimes in the 1990s - in Rwanda and Sierra Leone - have already ended their work (in 2015 and 2013 respectively). The baton now passes to the International Criminal Court (ICC). Whatever the long-term prospects for the ICC, its work owes an incalculable debt to the example of its ad hoc single country precursors. In this strange way, the permanent International Criminal Court might prove to be Ratko Mladić’s most significant legacy: poetic justice of the highest order.

Norrie MacQueen is the author of several books on the United Nations, peace operations and humanitarian intervention. He is co-editor of the Oxford Handbook of United Nations Peacekeeping Operations which has recently appeared in paperback, and he is on the editorial board of the Journal of International Peacekeeping. He was part of the Democratic Governance Support Unit of the UN integrated peacekeeping mission in Timor-Leste during 2012 in the final phase of the operation. Norrie is a Contributing Editor at CABLE. He is on Twitter at: @NorrieMacQueen Mail him at: [email protected]

Feature image: Ratko Mladić, former commander of the Bosnian Serb Army, at his trial judgement at the ICTY, 22 November 2017. Image: ICTY [CC BY 2.0]